Stubbornness in the face of rapid technological change is a recipe for disaster

‘The Last Jedi is a marvel of cinematic touch … but for all the lightsabres, interstellar transport and spherical energy shields, the absence of any workable artificial intelligence was jarring’

We tell ourselves stories in order to learn. Kodak failed because its managers did not take digital photography seriously enough. Blockbuster died because its chief executive refused to invest in Netflix. Nokia disappeared because its executives were initially blind to the potential of the smartphone, and when they finally realised its importance, they stopped short by not cultivating enough app developers. We tell ourselves repeatedly that understanding the past will hold out the promise of making the future better.

No story is more captivating for managers than a grand theory about “accelerated changes”. It once took the landline telephone 75 years to reach 50 million users, light bulbs 46 years and the television 22 years.

Surely our lives are changing faster than ever. In Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist’s Guide to Thriving in the Age of Accelerations, Thomas Friedman lays out why changes are speeding up everywhere.

“One of the hardest things for the human mind to grasp is the power of exponential growth in anything – what happens when something keeps doubling or tripling or quadrupling over many years – and just how big the numbers can get,” he writes while referring to Moore’s Law, an observation made by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, which states that the number of microchip transistors etched into a fixed area of a computer microprocessor would double every two years. Since transistor density correlates with computing power, the latter would also double every two years.

It is Moore’s Law that explains how a single iPhone today can summon more computing power than that of the entire Apollo spacecraft back in 1969. It is Moore’s Law that explains the plummeting cost of genome sequencing, making it so I can now receive a customised DNA report at my home from 23andMe for a mere US$99. It was Moore’s Law that gave rise to Google in Mountain View, California Facebook in Menlo Park, California, Amazon in Seattle, Washington, Snapchat in Venice, Los Angeles, California, Uber and Airbnb and Dropbox and Pinterest in San Francisco, California.

To keep up with Silicon Valley’s ultimate contraption, which will only speed things up even more, I was given the following advice: “In such a time, opting to pause and reflect, rather than panic or withdraw is a necessity. It is not a luxury or a distraction – it is a way to increase the odds that you’ll better understand and engage productively with the world around you.”

Thus the title of Friedman’s book, Thank You for Being Late. When a friend shows up late or an appointment gets delayed, those unplanned for, unscheduled times are the precious moments to gratefully pause and reflect.

The more the movie remained rooted in its original backdrop, the stranger the plot seems in 2018.

Snipers could have used thermal sights to find enemies, but did not. Computers could have corrected for missile range, lead, wind, munitions temperature, barometric pressure, but there was not any.

Conflicts should have been deadly silent; but instead, the intergalactic conflict was fought on running feet and with swinging arms. Pilots were prized for their brilliance in dodging bullets and missiles.

There were no radar lock-on auto rockets. The powerful weapons were powerlessly imprecise.

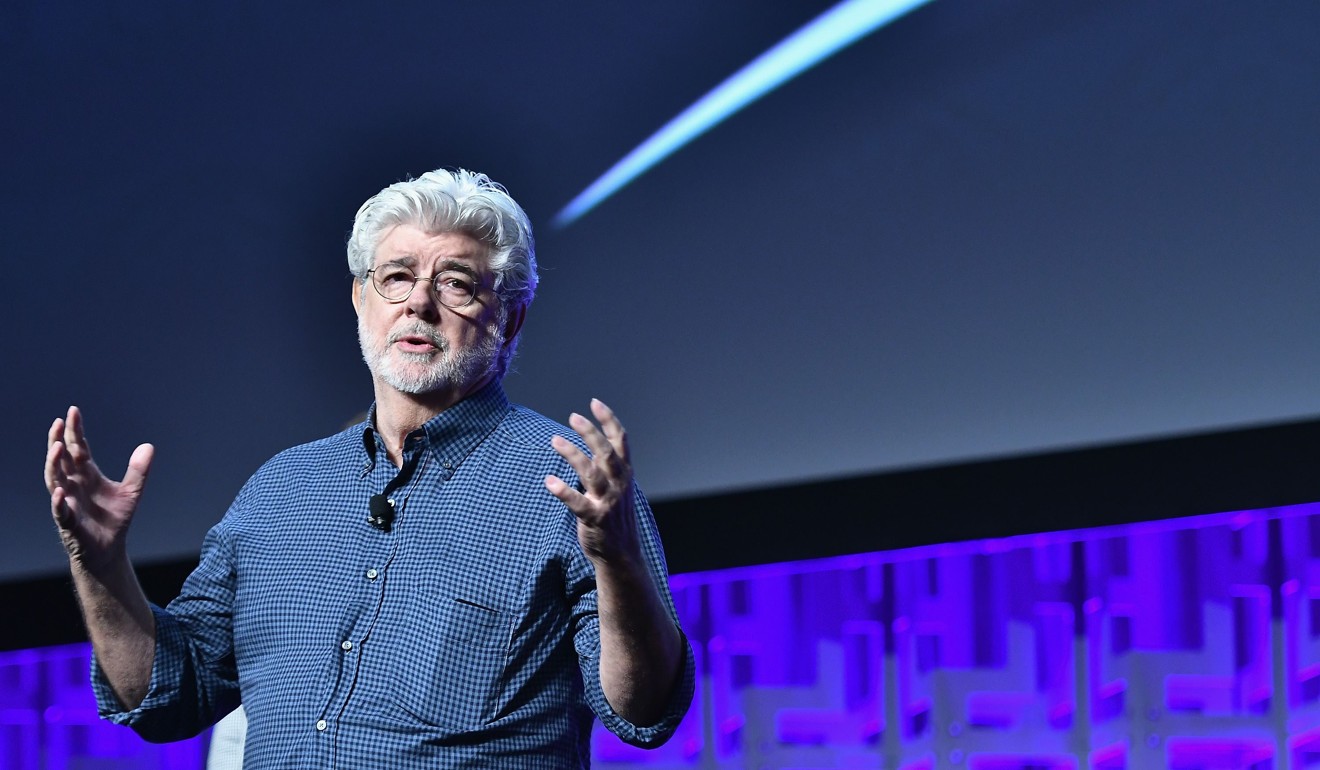

It was in some ways a predictable cinematic slip. When George Lucas released the first of the stand-alone Star Wars films in 1977, it was the era of atomic power and nuclear technologies that exuded glamour and excited the imagination. What had been accelerating, as a story in the public mind, was energy – a cheap, abundant, limitless and clean source of power. The Three Mile Island accident and Chernobyl disaster were years away.

That year, in 1977, the world’s first personal computer, the Commodore PET, debuted at the winter Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. Apple Computers was incorporated in January. With the exception of Gordon Moore, few predicted a 50-year exponential growth in computing power.

One last pause. Outside the theatre, in the AMC’s lobby area, was an IMAX virtual reality centre. Through virtual reality headsets, movie-goers could play the intergalactic pilots, dodging bullets and missiles and fighting enemies with swinging arms using hand-held remote controllers. “Oh my God, I can’t see!” screamed an eight-year-old. “Wait, this thing doesn’t work?” A technician scurried up and restarted a computer screen, from which a cable went up to the crane in the ceiling and dangled back down to the VR headsets.

When a friend shows up late or an appointment gets delayed, those unplanned for, unscheduled times are preciously the moments to thankfully pause and reflect

The kid was also wearing a backpack, which I was later told was the computer itself stuffed with batteries. I did not ask how much it weighed, but I did check the file size requirements of a typical VR game. The industry norm would suggest a machine with a storage space of somewhere between 2,000 to 3,000 gigabytes. Three thousand GB would be equivalent to approximately 4,500 CD-ROMs. That is 3,000 hours, or 125 days, of non-stop Netflix streaming. It occurs to me that the exponential growth in computing power has been met by an exponential growth in consumer demand. Nothing will ever be good enough. The kid was complaining.

The danger of the story of accelerated change is not so much that we misplace what is truly accelerating, but that we forget about the unchanging – the stubbornness of human nature. Hubris-led disasters have bankrupted all public tolerance for peacetime use of nuclear technology and, in more recent years, genetically modified crop technology. Will Moore’s Law come to an end, not because of technological limitations but because of a hubris-led artificial intelligence disaster? The unchanging is the most unsettling.

Howard Yu is professor of strategy and innovation at IMD